James Paynter

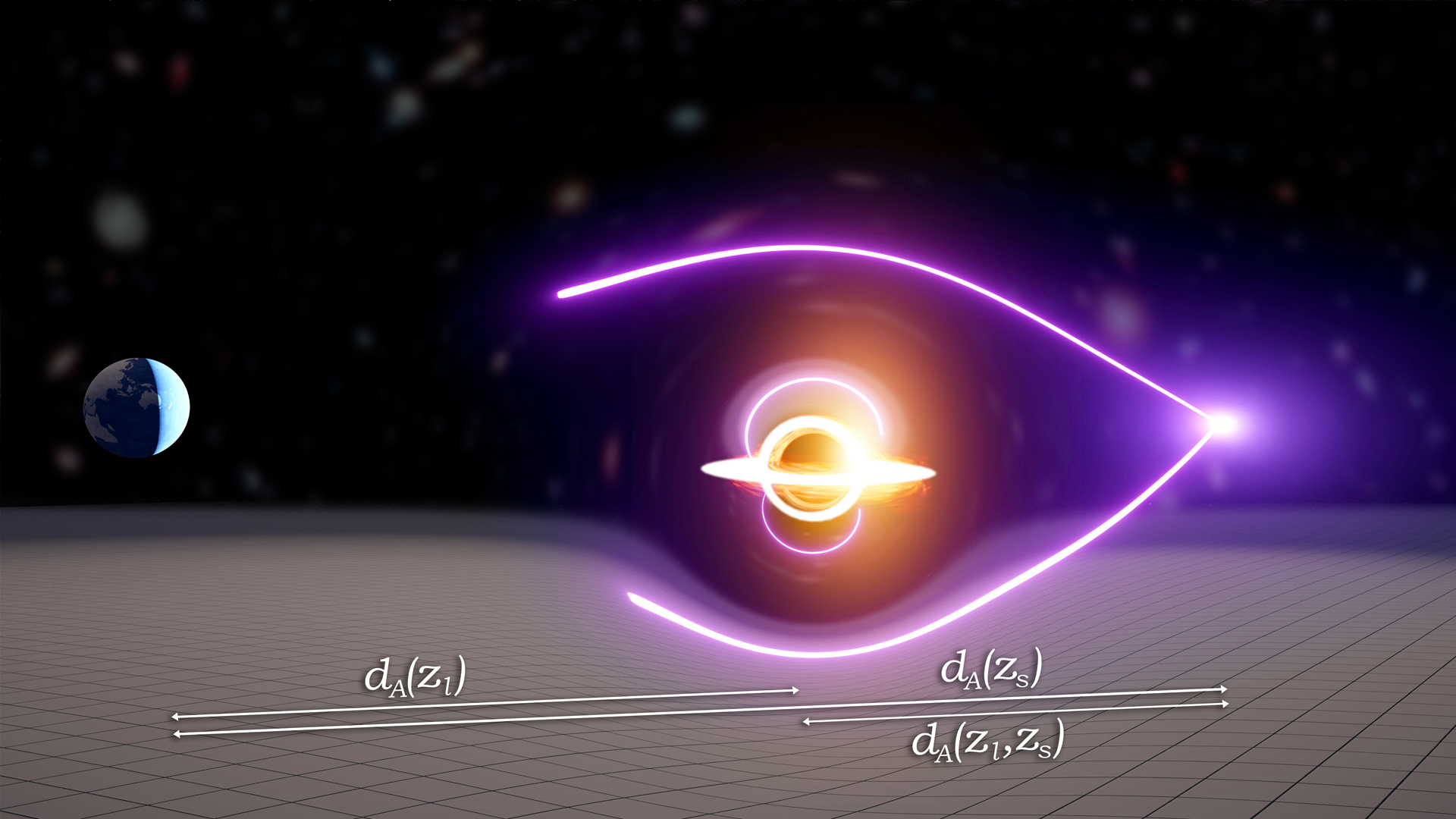

Above: Artist's impression of a gamma-ray burst gravitationally lensed by a black hole (Carl Knox).

Gravitational Lensing of Gamma-Ray Bursts

I have spent the past 3 years studying the gravitational lensing of gamma-ray bursts. In this project I uncovered what is likely to be the first gravitationally lensed gamma-ray burst, published in collaboration with Rachel Webster and Eric Thrane. I developed the software package PyGRB to do this.

Gamma-Ray Bursts

Gamma-ray bursts are generated when either a massive star collapses at the end of its life, or during the merger of a pair of neutron stars. Both events result in a black hole. Rapid infall of leftover stellar material onto the newly formed black hole launches ultra-relativistic bipolar jets about the rotation axis. These jets then emit the light which we receive as gamma rays.

In the early 90's there was a lot of interest in determining if gamma-ray bursts are signals from within our galaxy or cosmological (other, distant galaxies). The BATSE experiment was launched in 1990 to determine this very thing, and soon found that they were indeed cosmological signals. As cosmological sources must be gravitationally lensed some fraction of the time, many authors sought to find a lensed gamma-ray burst, but none were discovered. There was particular interest in black holes of 100 - 1 million solar masses, which had not yet been discovered. The short duration of gamma-ray bursts meant they could probe such low mass gravitational lenses.

Below: Side schematic of a gravitationally lensed gamma-ray burst (Carl Knox).

Gravitational Lensing

The chance alignment of a lens with a distant source results in a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing. Light from the source travels around the lens object, in our case an intermediate mass black hole, and is deflected by its gravitational field back towards the observer. In the simplest case, two paths are created which reach the telescope. Two paths equates to two images, and having travelled different distances, they spend different amounts of time reaching Earth. Despite travelling many billions of light-years to reach us, this difference in arrival time is just 400ms in our case. The path which traverses deeper into the potential well — closer to the black hole — experiences a stronger time dilation, and thus arrives later than the other image. The time delay, in addition to the ratio of the brightness of the two images (the magnification ratio), gives us an estimate for the mass of the lens. The most likely time delay roughly scales as 50 seconds per million solar masses.

Above: Artist's impression of a (long) gamma-ray burst generated by a core-collapse supernova being gravitationally lensed by a mystery object (James Paynter).

The Detection.

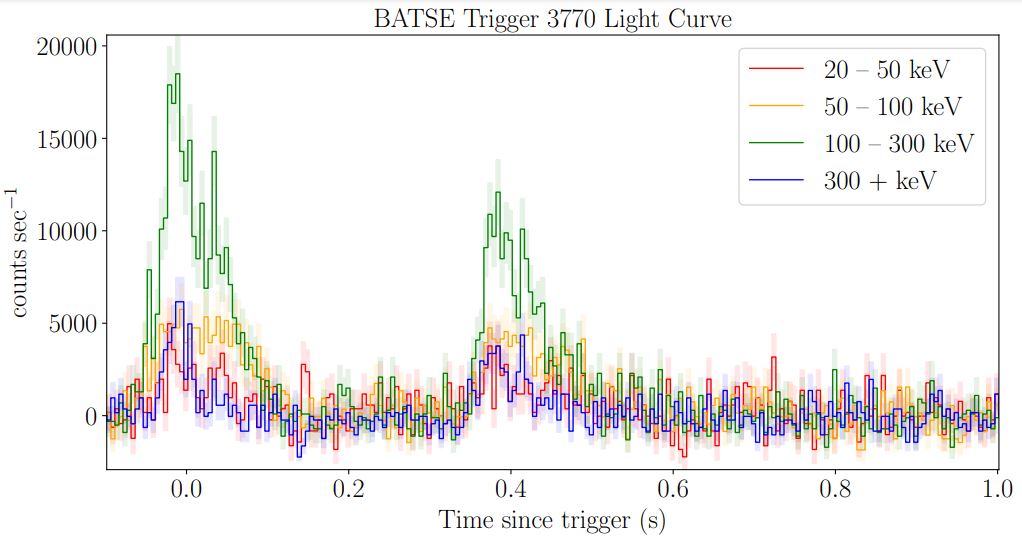

We search the BATSE catalogue for gravitationally lensed gamma-ray bursts. We focus on events occuring within the same observation, limiting our maximum time delay to about 4 minutes. We find one lensed gamma-ray burst, GRB 950830. From the time delay of 400ms, and magnification ratio of ~0.67, we infer a lens mass of $$(1+z_l)M_l = 5.5^{+1.7}_{-0.9}\times 10^4 M_\odot,$$ (solar masses).

Below: The light-curve of GRB 950830.

So, What was the Gravitational Lens?

There are 3 compact astrophysical objects in this mass range: globular clusters, dark matter haloes, and intermediate mass black holes.

We find that the number density of globular clusters is simply too low for it to have been gravitationally lensed by one of these. We would have to observe many gravitational lensing events for objects of this mass before we would begin to think a globular cluster was responsible for just one of them.

On the other hand, dark matter haloes and subhaloes are extremely numerous. But they are not compact enough to have the focusing power to create two images. The dark matter is too diffuse, only larger mass haloes have densities high enough to create multiple images via gravitational lensing.

We arrive at the conclusion that this object must have been an intermediate mass black hole.

Detecting intermediate mass black holes

If a black hole is not accreting matter, it is quite difficult to detect, as by name and nature they are black. Only the effects of their gravity can betray the existence of a quiescent black hole. In this case, it is an intermediate mass black hole which has gravitationally lensed a more distant gamma-ray burst in a fortuitous cosmic alignment of the source, lens and observer.

Intermediate mass black holes are an observationally unexplored region of parameter space in the black hole mass spectrum. They are loosely defined as filling in the mass gap from ~100 solar masses to 100,000 solar masses.

Stellar black holes (10 - 100 solar masses) form when the most massive stars end their lives in violent supernova explosions. Their subsequent growth and mergers are detectable as x-ray binaries / microquasars and via gravitational waves, respectively. We know supermassive black holes (100,000 - billions and billions of solar masses) exist in the hearts of every galaxy.

The question is, are these two distinct populations? Or is there a continuous range of black holes all the way from 10 solar masses up to one billion or more?

The Intermediate Mass Black Hole Population

The probability of observing a gravitational lensing event is proportional to the number of possible lenses in the sky. More lenses equates to more lensing. Based on having observed 1 gravitational lensing event in ~2,700 analysed bursts, we determine the space density of \(n_\text{imbh}\approx 2.3^{+4.9}_{-1.6}\times10^{3} \text{ Mpc}^{-3}\) (90% credibility).

Our galaxy formed from a region of space roughly 20 Mpc3, thus we find that there are ~46,000 intermediate mass black holes in the neighbourhood of the Milky Way. The Milky Way itself is much smaller, but we do not know how these objects are distributed in space. They could be concentrated in the core or disk of galaxies or they could be freely floating in intergalactic space.

What is the significance of this result?

It is important to discover these objects to fill the observational gap between stellar black holes and supermassive black holes. Currently, we do not know how supermassive black holes are able to grow to such huge masses within the age of the universe, there is simply not enough stuff for them to accrete, nor enough time. If a seed population of intermediate mass black holes exist, it begins to fill in this gap. Where the intermediate mass black holes came from is another matter... they may be formed from the merger and subsequent collapse of massive, hydrogen-pure stars in the early universe, or they may be older, primordial black holes formed during the very first phases of the universe.

First intermediate mass black hole discovered?

There are many intermediate mass black hole discovery papers, each claiming to be the first. I am not familiar enough with these papers to comment on the veracity of each of these detections, which I instead leave as an exercise for the reader. What I will say is that to the best of my knowledge, we have:

- First discovery of a gravitationally lensed gamma-ray burst.

- First determination of the number density of intermediate mass black holes.